Mathematical Foundations

If you are an absolute beginner in mathematics, you can take a look to my article on the Mathematical Language.

Prime numbers

Mathematically, a prime number can be defined precisely as follows:

A natural number \(p\) greater than 1 is called prime if it has exactly two positive divisors, 1 and itself. Formally:

Usually, we define the set of prime numbers as $$ \mathbb{P} = \left\{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, \dots\right\} $$

Examples

- 7 is prime: divisors are {1, 7}

- 12 is NOT prime: divisors are {1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12}

Exercices

1| Is 92 prime ?

Solution

No, 92 is NOT prime : Divisors are {1, 2, 4, 23, 92}

2| Is 2 prime ?

Solution

Yes, 2 is prime : Divisors are {1, 2}

3| Is 209 prime ?

Solution

No, 209 is NOT prime : Divisors are {1, 11, 19, 209}

4| Is 19 prime ?

Solution

Yes, 19 is prime : Divisors are {1, 19}

Short introduction to modular arithmetic

In mathematics, modular arithmetic is a system of arithmetic operations for integers, where numbers "wrap around" when reaching a certain value, called the modulus.

The modern approach was developed by Carl Friedrich Gauss in his book Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, published in 1801.

The Clock Analogy

One easy way to introduce modular arithmetic is to look at a clock.

When it's 8 o'clock and you add 5 hours, it becomes 1 o'clock (not 13 o'clock). This is because time "wraps around" after 12 hours.

We can represent this mathematically as: $$ 8 + 5 \equiv 1 \pmod{12} $$

Congruence

\(\forall n \in \mathbb{N},\ n > 1, \forall a, b \in \mathbb{Z},\) We say that \(a\) and \(b\) are congruent modulo \(n\) if \(n \mid (a-b)\), which is denoted by \(a \equiv b \pmod{n}\)

When we divide \(a\) by \(n\), we get: $$ a = nq + r \quad \text{where } 0 \leq r < n $$ We write: \(a \equiv r \pmod{n}\), and \(r\) is called the remainder.

Example

Let \(n\) = 5, \(a\) = 17 and \(b\) = 2:

We calculate :

Since \(5|15\), we have: $$ 17 \equiv 2 \pmod{5} $$

Alternative Definition

Another way to define the congruence is: $$ a \equiv b \pmod{n} \leftrightarrow \exists k \in \mathbb{Z}, a = kn + b\ $$ This means \(a\) and \(b\) have the same remainder when divided by \(n\).

Exercices

Is it true? \(100 \equiv 5 \pmod{50}\)

Solution

False, Because \(100 = 2\cdot50 + 0\), so \(100 \equiv 0 \pmod{50}\)

\(15 \equiv 3 \pmod{12}\)

Solution

True, Because \(15 = 12\cdot1 + 3\), so \(15 \equiv 3 \pmod{12}\)

\(9 \equiv 19 \pmod{10}\)

Solution

True, Because \(19 - 9 = 10\), and \(10 \mid 10\), so \(9 \equiv 19 \pmod{10}\)

\(46 \equiv -4 \pmod{50}\)

Solution

True, Because \(46 = 50 \cdot (1) + (-4)\) so \(46 \equiv -4 \pmod{50}\)

\(11 \equiv 5 \pmod{7}\)

Solution

False, Because \(11 = 7 \cdot 1 + 4\), so \(11 \equiv 4 \pmod{7}\)

Properties of Modular Arithmetic

If \(a \equiv b \pmod{n}\) and \(c \equiv d \pmod{n}\), then:

- \(a + c \equiv b + d \pmod{n}\)

- \(a - c \equiv b - d \pmod{n}\)

- \(a \cdot c \equiv b \cdot d \pmod{n}\)

- \(a^k \equiv b^k \pmod{n}\) for any \(k \in \mathbb{N}\)

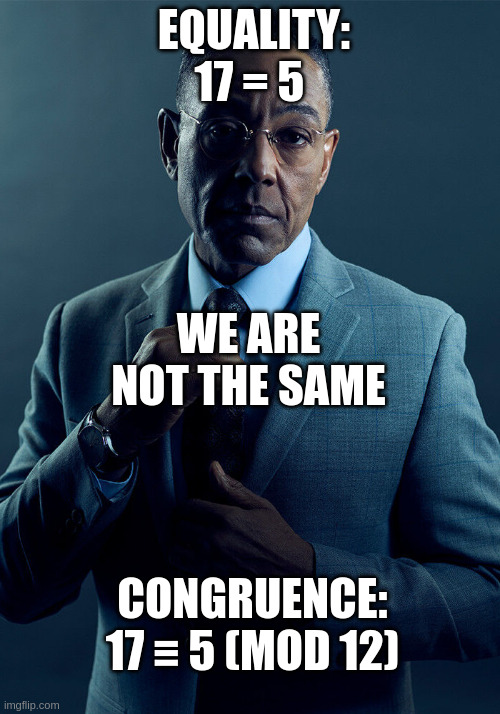

Why use "\(\equiv\)" instead of "\(=\)"?

In modular arithmetic, we use the symbol "\(\equiv\)" (congruence) rather than "\(=\)" (equality) because:

-

The "\(=\)" sign means exact equality: the two numbers or expressions are exactly the same.

Example:

\(7 + 3 = 10\), the sum is exactly 10.

-

The "\(\equiv\)" sign means congruence modulo n: two numbers are congruent modulo \(n\) if they leave the same remainder when divided by \(n\).

We write:

$$ a \equiv b \pmod{n} $$ which is equivalent to

$$ n \mid (a-b) $$ In other words, \(a\) and \(b\) have the same remainder modulo \(n\).Example:

\(17 \equiv 5 \pmod{12}\)

Because \(17 - 5 = 12\) is divisible by 12. Here, 17 and 5 are not equal, but they are congruent modulo 12.

-

Summary:

- "\(=\)" → exact equality

- "\(\equiv\)" → equality modulo \(n\) (same remainder)

Greatest Common Divisor (GCD)

The GCD of two integers \(a\) and \(b\) is the largest positive integer that divides both \(a\) and \(b\). Usually, we can write the GCD of \(a\) and \(b\) as \(\gcd(a, b)\)

Example:

\(\gcd(48, 18) = 6\)

Because \(18 = 2 \cdot 3^2\) and \(48 = 2^4 \cdot 3\). The common factors are \(2 \cdot 3 = 6\), so \(\gcd(48, 18) = 6\).

Coprime Numbers

Two integers \(a\) and \(b\) are called coprime (or relatively prime) if : $$ \gcd(a, b) = 1 $$ This means they share no common factors other than 1.

Examples:

15 and 28 are coprime:

- Because \(15 = 3*5\) and \(28 = 7 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 = 7 \cdot 2^2\), 15 and 28 don't share common factor, \(\gcd(15, 28) = 1\), so 15 and 28 are coprime.

15 and 25 are NOT coprime:

- Because \(15 = 3 *5\) and \(25=5 \cdot 5\), 15 and 25 have 5 in common factor, \(\gcd(15,25) = 5\), so 15 and 25 are NOT coprime.

Exercices

1| Calculate \(\gcd(125, 15)\)

Solution

We start by calculate the decomposition in prime factor of 125 and 15

- \(125 = 5 * 25 = 5 * 5 * 5 = 5^3\)

- \(15 = 5 * 3\)

125 and 15 has 5 in common, so \(\gcd(125, 15) = 5\)

2| are 840 and 945 coprime ?

Solution

We start by calculate \(\gcd(840, 945)\), the decomposition in prime factor of 840 and 945 are:

- \(840 = 2 \cdot 420 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 210 = 2^2 \cdot 2 \cdot 105 = 2^3 \cdot 5 \cdot 21 =2^3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7 \cdot 3 = 2^3 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7\)

- \(945 = 5 \cdot 189=5 \cdot 3 \cdot 63 = 5 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 21 = 5 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 3 \cdot 7=3^3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7\)

840 and 945 have \(3, 5, 7\) in common, \(\gcd(840, 945) = 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7 = 105\) so 840 and 945 are not coprime

3| are 840 and 121 coprime ?

Solution

We start by calculate \(\gcd(840, 121)\), the decomposition in prime factor of 840 and 121 are:

- \(840 = 2 \cdot 420 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 210 = 2^2 \cdot 2 \cdot 105 = 2^3 \cdot 5 \cdot 21 =2^3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7 \cdot 3 = 2^3 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7\)

- \(121 = 11\cdot11 = 11^2\)

840 and 121 don't have common factors, \(\gcd(840, 121) = 1\) so 840 and 121 are coprime.

Euclidean Algorithm

The Euclid's algorithm is an efficient method for computing the GCD of two integers.

The main idea of Euclid's algorithm is : $$ \gcd(a,b) = \gcd(b, a \bmod b) $$ The algorithm repeatedly replaces the larger number with the remainder of dividing the larger by the smaller, until one number becomes zero.

The algorithm is based on this key property :

Lemma: If \(a = bq + r\), then \(\gcd(a, b) = \gcd(b, r)\)

Proof sketch: - Any common divisor of \(a\) and \(b\) must also divide \(r = a - bq\) - Any common divisor of \(b\) and \(r\) must also divide \(a = bq + r\) - Therefore, the sets of common divisors are identical, so their GCD is the same

Step-by-Step Example

Let's compute \(\gcd(48, 21)\):

| Step | \(a\) | \(b\) | Remainder \(r\) (\(a \bmod b\)) | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | 21 | 6 | \(48 = 21 \cdot 2 + 6\) |

| 2 | 21 | 6 | 3 | \(21 = 6 \cdot 3 + 3\) |

| 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | \(6 = 3 \cdot 2 + 0\) |

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Answer |

When \(b = 0\), we stop. The GCD is \(a=3\), so \(\gcd(48, 21) = 3\).

Another Example

Let's compute \(\gcd(924, 630)\)

So \(\gcd(924, 630) = 42\)

Time Complexity

The Euclidean algorithm is really efficient. The time complexity is \(O(\log(\min(a, b)))\), where \(a\) and \(b\) are the two integers of which you are finding the Greatest Common Divisor.

For small numbers, finding the GCD via prime factorization works well. However, for large numbers (like in RSA), prime factorization becomes computationally infeasible. This is why we use the Euclidean Algorithm, which is efficient even for huge numbers.

Python Implementation

def gcd(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""

Compute the Greatest Common Divisor of a and b

using the Euclidean Algorithm. If all arguments

are zero, then the returned value is 0.

Args:

a (int): First integer

b (int): Second integer

Returns:

int: The GCD of a and b (always positive)

"""

# Absolute function

a, b = abs(a), abs(b)

while b != 0:

a, b = b, a % b

return a

The algorithm can also be written recursively:

def gcd(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""

Compute the Greatest Common Divisor of a and b

using the Euclidean Algorithm. If all arguments

are zero, then the returned value is 0.

Args:

a (int): First integer

b (int): Second integer

Returns:

int: The GCD of a and b (always positive)

"""

if b == 0:

return abs(a)

return gcd(b, a % b)

Python also provides a built-in function in the math module:

import math

math.gcd(39, 3) # returns 3

However, understanding the algorithm is crucial for the Extended Euclidean algorithm, which we'll need for RSA key generation.

Exercices

- Compute \(\gcd(987, 462)\) by hand using the Euclidean Algorithm.

Solution

The Euclidean Algorithm:

So, \(\gcd(987, 462) = 21\)

Extended Euclidean Algorithm

The Extended Euclidean algorithm is an extension to the Euclidean algorithm, and computes, in addition the Greatest Common Divisor of integers \(a\) and \(b\), but also finds integers \(x\) and \(y\) such that: $$ ax + by = \gcd(a,b) $$ This equation is know as Bézout's Identity.

The Extended Euclidean Algorithm works by performing the Regular Euclidean Algorithm in the forward phase, then working backward to express the GCD as a linear combination of \(a\) and \(b\).

Step-by-Step Examples

Let's find \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(48x + 18y = \gcd(48, 18)\).

Forward Phase (Regular Euclidean Algorithm):

| Step | \(a\) | \(b\) | Quotient \(q\) | Remainder \(r\) | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | 18 | 2 | 12 | \(48 = 18 \cdot 2 + 12\) |

| 2 | 18 | 12 | 1 | 6 | \(18 = 12 \cdot 1 + 6\) |

| 3 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 0 | \(12 = 6 \cdot 2 + 0\) |

So \(\gcd(48, 18) = 6\)

Backward Phase (Finding coefficients): Now we work backwards to express 6 as a combination of 48 and 18:

From the penultimate equation:

So \(x = -1\), \(y = 3\)

Another example

Let's find \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(240x + 46y = \gcd(240, 46)\) Forward Phase:

Backward Phase: From the penultimate equation:

so \(x = -9\) and \(y=47\).

Python implementation

One easy way to implement the Extended Euclidean algorithm is recursively:

def extended_euclidean(a: int, b: int) -> tuple[int, int, int]:

"""

Computes the GCD of two integers a and b, as well as the coefficients x and y

of Bézout's identity: a * x + b * y = gcd(a, b).

Args:

a (int): The first integer.

b (int): The second integer.

Returns:

tuple[int, int, int]: A tuple containing:

- gcd (int): the greatest common divisor of a and b,

- x (int): the coefficient of a in Bézout's identity,

- y (int): the coefficient of b in Bézout's identity.

"""

if b == 0:

return a, 1, 0

else:

gcd, x, y = extended_euclidean(b, a % b)

x, y = y, x - (a // b) * y

return gcd, x, y

it also possible to implement it in a iterative way:

def extended_euclidean(a: int, b: int) -> tuple[int, int, int]:

"""

Computes the GCD of two integers a and b, as well as the coefficients x and y

of Bézout's identity: a * x + b * y = gcd(a, b).

Args:

a (int): The first integer.

b (int): The second integer.

Returns:

tuple[int, int, int]: A tuple containing:

- gcd (int): the greatest common divisor of a and b,

- x (int): the coefficient of a in Bézout's identity,

- y (int): the coefficient of b in Bézout's identity.

"""

x0, x1, y0, y1 = 1, 0, 0, 1

while b:

q, a, b = a // b, b, a % b

x0, x1 = x1, x0 - q * x1

y0, y1 = y1, y0 - q * y1

return a, x0, y0

Exercices

1| Find \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(120x + 45y = \gcd(120, 45)\)

Solution

Let's find \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(120x + 45y = \gcd(120, 45)\)

Forward Phase:

Backward Phase:

So \(x = -1\) and \(y = 3\).

2| Find \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(21x + 14y = gcd(21, 14)\)

Solution

Let's find \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(21x + 14y = \gcd(21, 14)\)

Forward Phase:

Backward Phase:

So \(x = 1\) and \(y = -1\).

Modular Inverse

The Modular Inverse of \(a\) modulo \(n\) is an integer \(x\) such that: $$ a \cdot x \equiv 1 \pmod{n} $$ We write: $$ x \equiv a^{-1} \pmod{n} $$

Example:

\(3 \cdot 5 = 15 \equiv 1 \pmod{7}\), So \(3^{-1} \equiv 5 \pmod{7}\)

Existence and Uniqueness

Existence: The modular inverse exists if and only if \(\gcd(a, n) = 1\) - If \(\gcd(a, n) \neq 1\), then \(a^{-1}\pmod{n}\) doesn't exist

Uniqueness: When the inverse exists, it is unique modulo \(n\) - This means there is exactly one value \(x\) in the set \(\{1, 2, \dots, n-1\}\) such that \(a \cdot x \equiv 1 \pmod{n}\) - Any other solution is congruent to this value modulo \(n\)

Why not 0? Note that \(0\) is excluded because \(a \cdot 0 = 0 \not\equiv 1 \pmod{n}\) for any \(a\).

Formally: $$ \exists! x \in {1, 2, \dots, n-1} \text{ such that } ax \equiv 1 \pmod{n} $$

Computing Modular Inverses

There are several methods to compute modular inverses:

Brute Force

For small moduli, we can try all values in \(\left\{1, \dots, n-1\right\}\) until we find one that satisfies \(a \cdot x \equiv 1 \pmod{n}\).

Example

Find \(7^{-1} \pmod{11}\) We test each value systematically:

| \(x\) | \(7 \cdot x\) | \(7 \cdot x \bmod 11\) | Is it \(\equiv 1\)? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 7 | No |

| 2 | 14 | 3 | No |

| 3 | 21 | 10 | No |

| 4 | 28 | 6 | No |

| 5 | 35 | 2 | No |

| 6 | 42 | 9 | No |

| 7 | 49 | 5 | No |

| 8 | 56 | 1 | Yes |

Therefore, \(7^{-1} \equiv 8 \pmod{11}\)

Verification: \(7 \cdot 8 = 56 = 11 \cdot 5 + 1 \equiv 1 \pmod{11}\)

Python Implementation

def modular_inverse_brute_force(a: int, n: int) -> int:

"""

Compute the modular inverse of a modulo n using brute force.

Only practical for small values of n.

Args:

a (int): The integer whose inverse is sought

n (int): The modulus

Returns:

int: The modular inverse of a modulo n

Raises:

ValueError: If the inverse doesn't exist (gcd(a,n) ≠ 1)

"""

a = a % n # Normalize a to be in range [0, n-1]

# Try all possible values from 1 to n-1

for x in range(1, n):

if (a * x) % n == 1:

return x

# If we reach here, no inverse was found

raise ValueError(f"Modular inverse doesn't exist: gcd({a}, {n}) ≠ 1")

Extended Euclidean Algorithm

The most efficient method is using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm (see Extended Euclidean Algorithm).

The Extended Euclidean algorithm finds integers \(x\) and \(y\) such that: $$ ax + ny = \gcd(a, n) $$If \(\gcd(a, n) = 1\), then: $$ ax + ny = 1 \leftrightarrow ax \equiv 1 \pmod{n} $$

So \(x\) is the modular inverse of \(a\) modulo \(n\)!

Python Implementation

def modular_inverse(a: int, n: int) -> int:

"""

Compute the modular inverse of a modulo n using Extended Euclidean Algorithm.

Args:

a (int): The integer whose inverse is sought

n (int): The modulus

Returns:

int: The modular inverse of a modulo n

Raises:

ValueError: If gcd(a,n) ≠ 1 (inverse doesn't exist)

"""

gcd, x, y = extended_euclidean(a, n)

if gcd != 1:

raise ValueError(f"Modular inverse doesn't exist: gcd({a}, {n}) = {gcd} ≠ 1")

return x % n # Ensure positive resultPython provides an easy way to compute modular inverses using the Euclidean Algorithm:

# To compute the modular inverse of a mod n

pow(a, -1, n)Examples

1 | Find \(3^{-1} \pmod{7}\) We need \(3x \equiv 1 \pmod{7}\)

Testing values:

So, \(3^{-1} \equiv 5 \pmod{7}\) This is the unique solution in \(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\).

Note

\(3 \times 12 = 36 \equiv 1 \pmod{7}\) is also true, but \(12 \equiv 5 \pmod{7}\), so it's the same solution.

2| Find \(7^{-1} \pmod{26}\) We check that 7 is coprime with 26: $$ \gcd(26, 7) = 1 $$

We need to find \(x\) such that \(7x \equiv 1 \pmod{26}\). \(x\) is necesseraly congru to one of the integers of \(\left\{0, 1,2, \dots, 25\right\} \pmod{26}\).

So, \(7^{-1} \equiv 15 \pmod{26}\) This is the unique solution in \(\{1, 2, \dots, 25\}\).

Note

\(119 \equiv 1 \pmod{26}\) is also true, but \(119 \equiv 15 \pmod{26}\), so it's the same solution.

3| Does \(3^{-1} \pmod{12}\) exists ? We check that 3 is coprime with 12: $$ \gcd(3, 12) = 3 $$ Since \(\gcd(3, 12) = 3 \neq 1\), the modular inverse does not exist. There is no integer \(x\) such that \(3x \equiv 1 \pmod{12}\).